The Battle for the Living Room 🛋️

But maybe not the one you think

Neighbors,

For the last several years, many a pundit has proclaimed YouTube “king of the living room” due to the platform’s dominant share of television watch time among streamers.

This isn’t an essay about that. This is an essay about creators, third spaces, and…coffee. Four observations:

1.

When coffeehouses first started popping up on the Arabian Peninsula in the fifteenth century, they weren’t known for their free WiFi. Coffeehouses were a place to meet—to play board games, listen to music, and take in oral stories. They became a breeding ground for thoughtful ideas, spaces where free and authentic discourse was welcomed and challenged.

Upon traveling across Persia, one French writer noted the liveliness of the coffeehouse scene:

“People engage in conversation, for it is there that news is communicated and where those interested in politics criticize the government in all freedom and without being fearful, since the government does not heed what the people say.”

With coffeehouses finding a strong footing in Constantinople, the Ottomans brought them to Eastern Europe. Serbia claims that the first “kafanas” started to pop up in the region during the Turkish reign, an entire century before their debut in London, Marseilles, or Vienna. Not only did coffeehouses foster political conversations, they also became a nexus point for relationships, business, and innovations to thrive:

“...deals were concluded, marriage agreements were made…these were the places where the audience saw the first film, the first theatre plays, and the first phone rang…”

By the nineteenth century, in Western Europe, artists and writers would often frequent coffeehouses; this theme carried over to the United States, where musicians like Bob Dylan led the 1960s folk revival throughout Italian espresso bars in Greenwich Village. These public spaces developed in step with thinkers and storytellers who wanted a more productive counterpart for boozy beer halls. It’s therefore the reason we consider coffee an “adult” drink to this day.

But coffeehouses weren’t the only cultural hubs brewing last century.1

2.

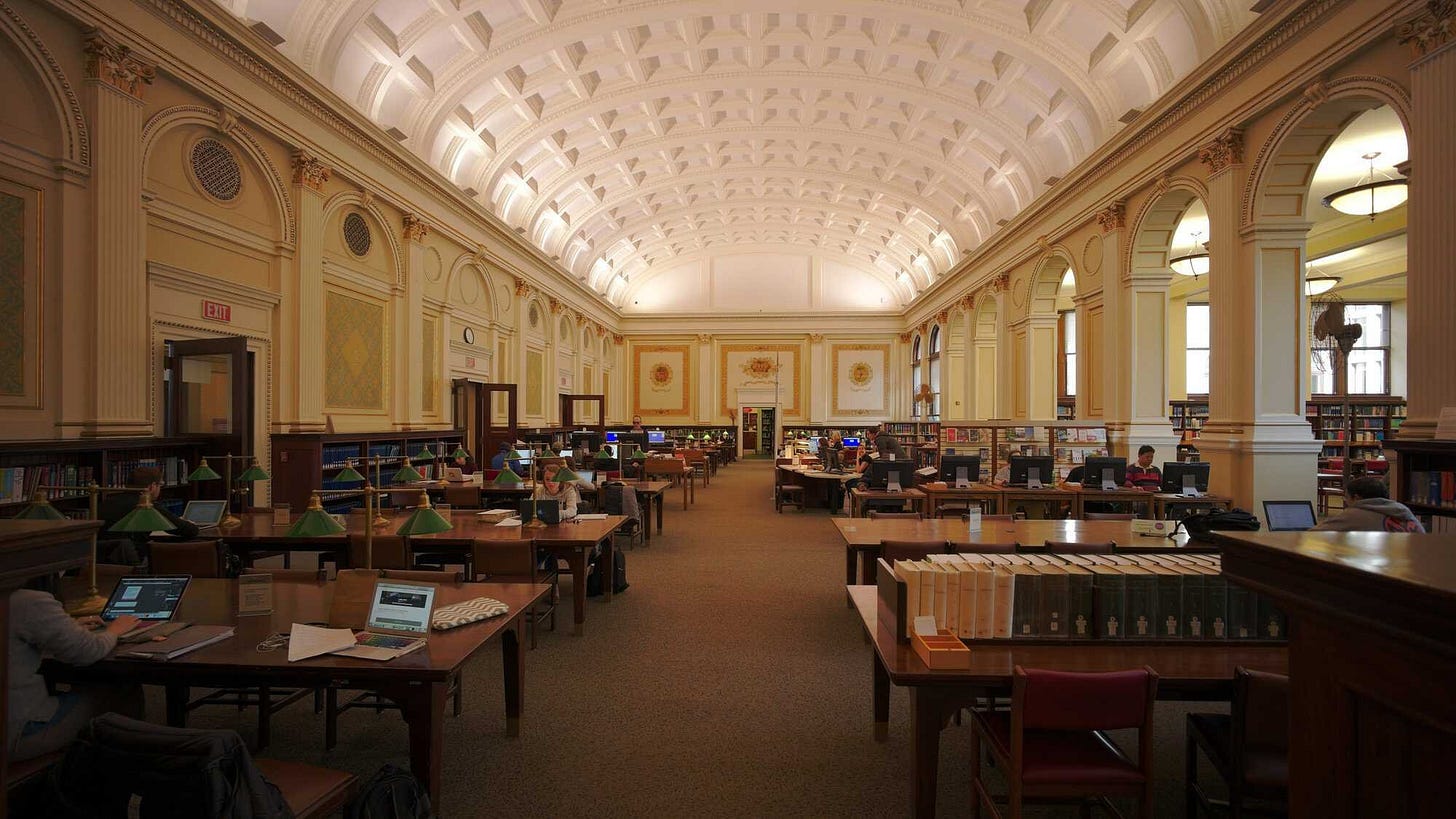

Steel baron Andrew Carnegie left a complicated legacy, accruing wealth via brutal means (see: The Homestead Strike). Yet he also deeply believed in philanthropy, giving away the modern equivalent of six billion dollars. One investment he stood behind was a public good that could truly serve anyone: libraries.

Over three thousand Carnegie libraries dot the world. They share similar architectural elements like high ceilings and big windows; this design was intentional, as the businessman wanted these spaces to feel like an “exalted experience,” a rich melting pot of knowledge and ideas. In turn, Carnegie dubbed his libraries “palaces for the people.”

This phrase served as inspiration for a 2018 book of the same name, written by American sociologist Eric Klinenberg. In it, the author argues that in order to “fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civil life,” there’s a lot we can learn from Carnegie’s libraries as an instance of “social infrastructure.”

Klinenberg defines social infrastructure as the physical places and organizations that shape the way we interact. It refers to a physical system in place, same as we have for telecommunications, water, or power. In his words, it’s “literal material structure that shapes our social lives.”

Through his research, Klinenberg found that when communities invest in social infrastructure like parks, bowling alleys, churches, and libraries, we are far more likely to repeatedly engage with other people around us, from friends and family to neighbors and strangers. Many American libraries offer ESL classes to non-native speakers.2 In major Chinese cities, it’s not uncommon to see hundreds of elderly people flock to “senior playgrounds.”

When these spaces are made more accessible to everyone, they also help us broaden our horizons, sparking interactions and encounters across the socioeconomic spectrum. Disagreements may arise from these experiences, albeit with a catch: Klinenberg notes they’re more likely to occur in a more respectful manner than elsewhere.

It seems obvious, right? Epidemiologists have firmly established a relationship between social connections, health, and longevity of life.

Look no further than creators. Most I talk to are introverts by nature. The impetus to upload is less about achieving fame or riches and more about broadcasting a beacon, finding other people who share the same interests and values.

The reason we’re driven to find community online, however, is because our public spaces are not designed and updated enough to accommodate our modern-day needs. In fact, most institutions are slashing budgets for social infrastructure out of an overarching belief that it’s no longer a priority and could serve more “efficient” purposes.

This stands in stark contrast to the mid-twentieth century, when families spent their Sundays bowling in leagues or reading together at the library. Over the last thirty years, we’ve poured our increased leisure time into watching TV, immediately changing our “interior decorating, relationships, and communities,” as Derek Thompson writes. When we do venture outside, oftentimes, the places we visit are in the private sector. Or, as Klinenberg states, “we pay to be part of public life.”

“You go shopping, it’s so much fun at first, and then you realize they’re asking you to spend money. Often, you don’t have that money.

And so there’s always this strange feeling of organizing public life around commercial things, which is it’s uplifting, and then a little bit hollow and frustrating, too.”

But to design spaces that feel welcoming, we first have to reach people where they’re already congregating.

3.

I first wrote a version of this essay in November 2019, one month before the first case of COVID was discovered and four months before lockdowns became a living reality for most Americans. My thesis has changed a lot over these last six years. I’m fortunate enough to have lived in three major cities—working, reading in, and exploring various cafes, parks, and libraries across the country.

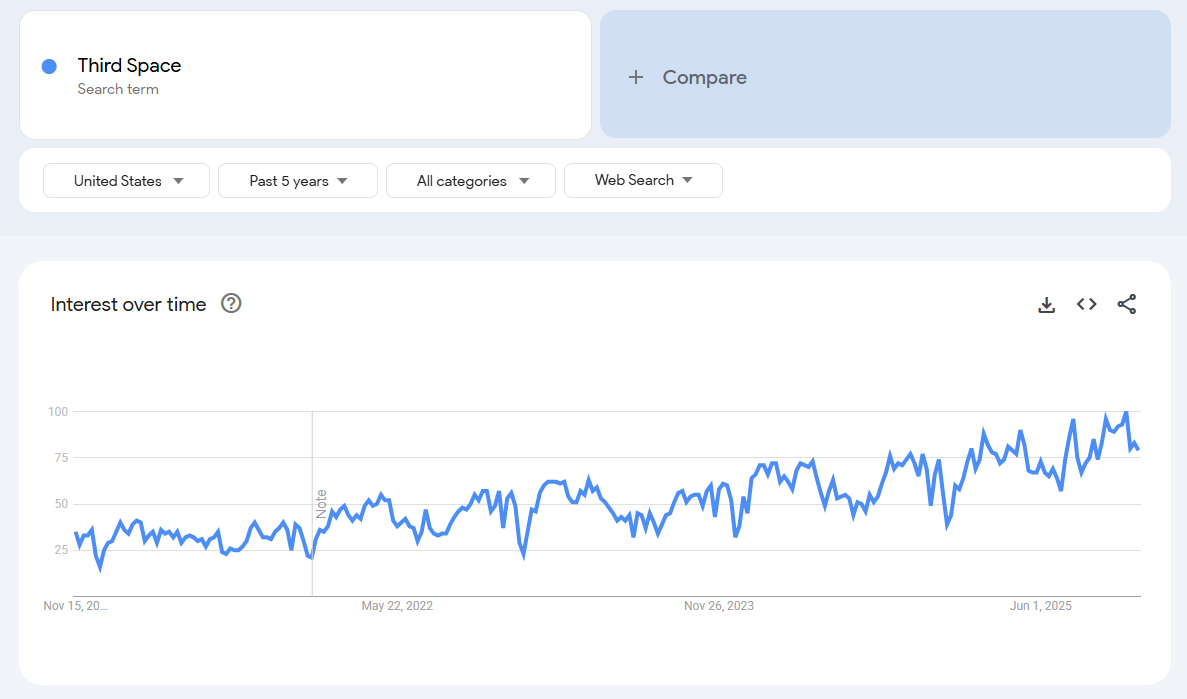

The main reason it’s evolved, though, is because it feels like the tide is turning. Per Google Trends, more people are searching the phrase “Third Space” than ever before.

And according to a recent study by The Financial Times, people are spending less time on social media, with usage peaking in 2022.

In this vein, Klinenberg believes that while libraries might feel like antiquated institutions, they present the best place—and model—to start refurbishing social infrastructure. Past investments in pure dollar sums, organizers need to aggressively do outreach, forming relationships with local leaders and understanding their neighborhoods.

Nevertheless, the path forward isn’t as black-and-white as TikTok bad, bowling alleys good. It’s about understanding how real community is formed through showing up consistently for each other and creating shared values. Arguing that the effort to bring people together through digital and physical means is more similar than we realize, one of the godfathers of online community, Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian, once told me this:

“If you were to bring a small group of people together that liked…jogging. You do it because you really like jogging, and you put up a flyer. And no one shows up for a while, then a couple of people show up.

Eventually, they bring some more people. Those people bring more people. All of a sudden, you’ve got a hundred-person jogging club with a culture, a shared history, experience. You have a community.

We as organisms understand how community-building works, yet we haven’t made the leap yet to understand it’s the exact same thing online.”

Creators like Yes Theory do understand this. The group tells powerful, human-centered stories every month; in turn, IRL “Yes Fam” meetups have popped up in cities around the globe (some attendees have even gotten married).

When I profiled Hank and John Green, they attribute their longstanding success to their passionate audience of “Nerdfighters.” The Greens famously upload two videos on their Vlogbrothers channel every week. With John consistently educating their audience about the world’s deadliest disease, tuberculosis, for the last half-decade, Nerdfighters have made real-world impact—donating over twenty-five million dollars and even mobilizing against Big Pharma.

My thesis has evolved over the years because I believe that when creators wield their influence in a positive fashion, they can play a major role in the next wave of social infrastructure development.3

4.

Upon opening the studio this year, something I set out to accomplish was building a “living room for the city”—one where creatives could meet as peers, swapping thoughts and ideas on everything from YouTube thumbnail feedback to book recs to local politics. It’s the type of space I always wanted to frequent when I first moved to Chicagoland as a wide-eyed teenager in 2017, and while we have a long way to go, I’d like to think we’ve taken moderate strides.

In 2025, we’ve hosted over a dozen events and hundreds of people. These events have included (but are not limited to):

Show Your Work! Intimate nights of feedback and conversation among ~10 creatives, sharing everything from short films to the first pages of their novels.

Short Story Long. A storytelling workshop—part instruction, part open mic—that left attendees laughing, crying, or both.

The Block Party. A quarterly hang full of fireside convos and live music, as we celebrate the release of each new edition of Creator Mag.

In regards to progress, it’s cool to see regulars now returning, again and again. But an offhand comment at a recent Show Your Work! really stuck out.

It was one attendee’s first time in the studio. Regarding the piece they were looking for feedback on, they told me they’d only ever shared it with their roommate. “But after watching your YouTube videos, I felt like I’d be comfortable sharing it here,” they told me.

That was pretty cool—to hear that the beacon we put out is finding the right people. And it reminded me of something else Alexis Ohanian said, in regards to the running club story:

If I told you that same story, and said, ‘What you need to do is hire some 21-year-old who also really likes jogging, have them post the flyer, show up every Sunday, organize the runs, do that for six months…and then you show up.’

You’d have no connection to those people.

Building social infrastructure takes real commitment, time I could be spending solely writing or editing videos. To borrow a phrase from Eric Klinenberg, it is not “efficient.” Nevertheless, we’re already seeing dividends, and it’s only Year One.

Sure, fostering community is good for any business. But when I look back at 2025, I’ll remember those late nights hosting people in the studio. Because we’re in business so that we can foster community.

We’ve been throwing several Show Your Work! nights of late because attendees always seem to walk away with a lot of great feedback and even better conversations.

Still, I’d love to know…

Past that, a lot goes into writing deep dives like this one. If you did enjoy it, consider sharing it with a friend. It goes a long way in supporting us on our mission.

P.S. Last blog, we reviewed the explosive, silly, scavenger hunt-focused docuseries Scav. You can read it here.

Thanks for reading! Shoot us a reply, comment, or DM if anything resonated with you in particular—we respond to them all.

Pun intended.

When I lived in DC, the local library even offered free dance classes.