Nothing Is Real 💊

Notes on the "clipping" economy

Neighbors,

I promise I’m not promoting conspiracy theories and/or red-pilled nihilism here. Treat this more as a commentary on authenticity in the age of clipping. Four observations:

1.

On September 13, 2024, a prominent finance creator on YouTube texted me this:

“I think a lot of people have heard rumors of campaigns & PACs paying influencers, but I don’t think many realize that this loophole is actively being used,” the finance creator, who’s becoming increasingly involved on Capitol Hill, wrote.

“Theoretically, a Super Pac or Kamala [Harris] could have given Taylor Swift a million dollars to make that Instagram post, or Trump could have given Nelk a bag for hosting him on their podcast - the crazy thing is that there is not any required transparency.”

I looked into this shortly afterwards and talked to a couple sources—including one agency founder who was brokering these types of deals during election season. As it turned out, the finance creator was right, and paid influencer endorsements had become big business.1

How was this legal? It’s a gray area. Think about when a creator verbally thanks a sponsor, or writes #ad in a caption. Typical brand partnerships are regulated by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which already struggles with proper oversight.2

But campaign finance laws are regulated by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), not the FTC. And while the former has strict rules regarding political ads across traditional media (like thirty second local TV spots), the FEC chooses not to regulate “organic” content produced by creators.3

Experts don’t believe anything will change over the course of the Trump administration. Between his crypto dealings and complimentary Qatari airplanes, this is one of the most corrupt presidents—if not the most corrupt president—in our nation’s history. Why would he regulate creators? Buying their endorsements keeps the grift going. Politics aren’t real.

2.

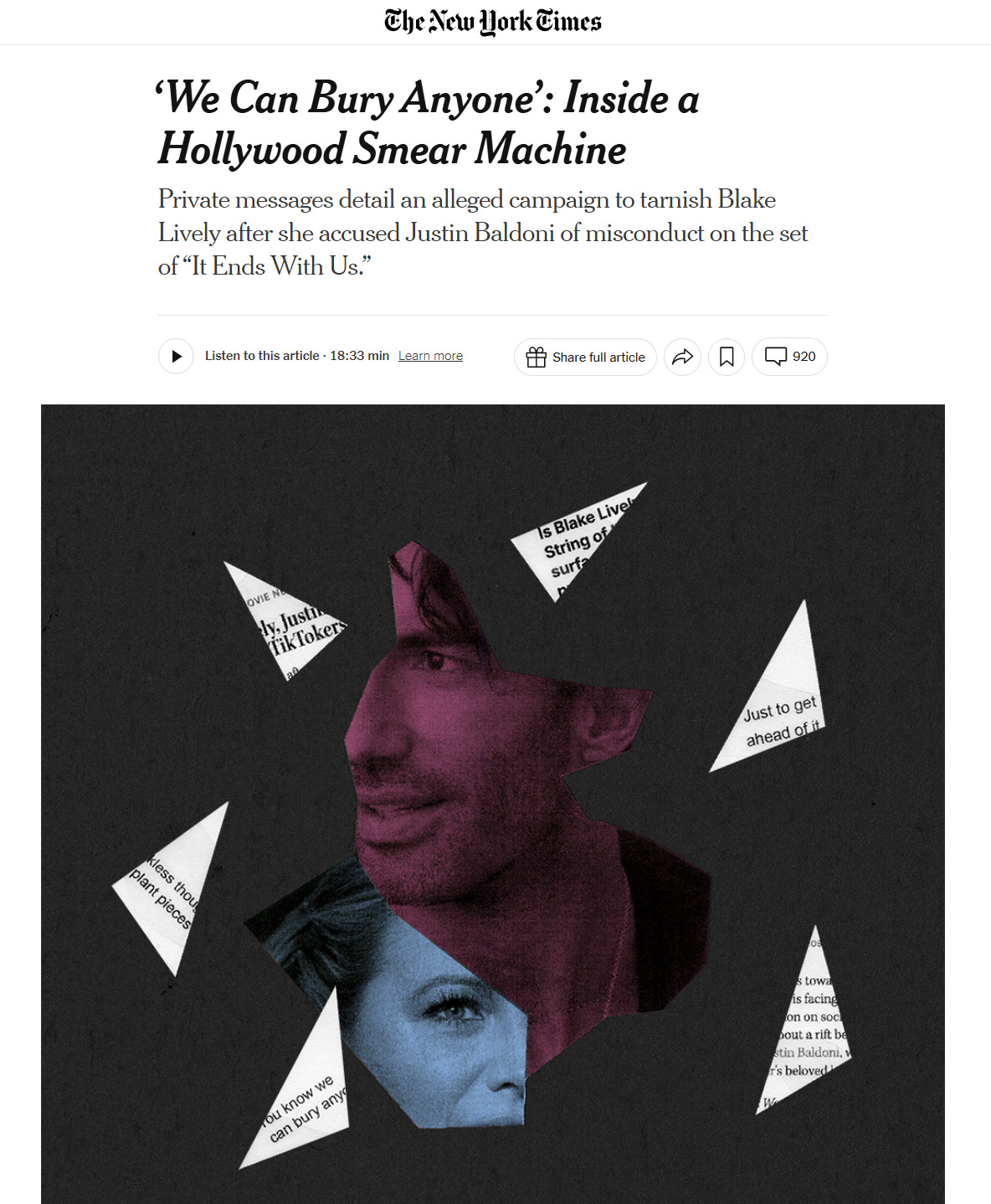

In December, The New York Times published a lengthy exposé of actors Blake Lively and Justin Baldoni’s disastrous working relationship, including Lively’s allegations of sexual harassment while filming their drama flick It Ends With Us (2024).

This isn’t the space to sift through the full timeline of this feud; Deadline already did this for us. Yet upon reading the NYT piece last year, what struck me is how it thrust modern “public relations” into the limelight.4

In this telling, crisis management expert Melissa Nathan (whose clients have included Johnny Depp, Drake, and Travis Scott) helped push stories that covered Lively negatively, tanking the actor’s reputation in an attempt to bury her forthcoming harassment allegations. On top of that, she hired Jed Wallace, a “hired gun” who claimed to have a “proprietary formula for defining artists and trends”:

There are references in emails to “social manipulation” and “proactive fan posting,” and text messages cite efforts to “boost” and “amplify” online content that was favorable to Mr. Baldoni or critical of Ms. Lively.

“We are crushing it on Reddit,” Mr. Wallace told Ms. Nathan.

When we read comment sections online, we all know that the person with a suspect handle chockful of numbers…probably isn’t real. But the sophistication of these networks has evolved from a crude bludgeon to a precise screwdriver. When wielded in capable hands, bot networks can slowly shift the perception of public figures— upvote by upvote, comment by comment.

A friend of mine who works with top creators has seen this in motion. He says celebrities like Taylor Swift employ similar practices; he’s shared his belief that foreign governments including Russia and Iran are behind a large percentage of something as seemingly innocuous as, say, your favorite YouTubers’ comment section.

PR, therefore, no longer looks like twenty-three-year-olds booking their clients’ late night appearances. No, public opinion is shaped by “digital strategists” like Jed Wallace, battle-tested gunslingers who can win the war online. Celebrities aren’t real.

3.

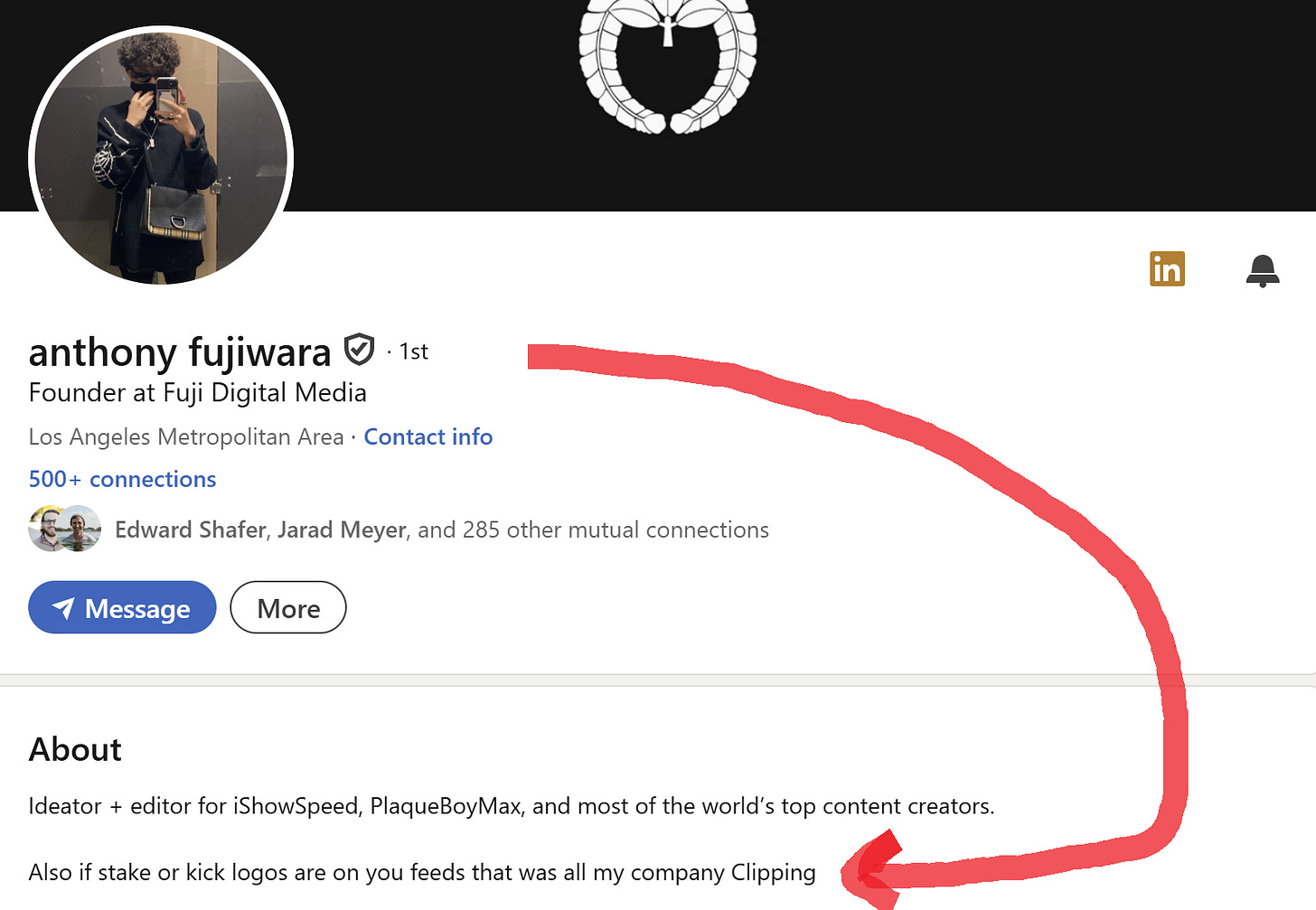

A couple weeks ago, The Los Angeles Times ran a profile on Anthony Fujiwara, the twenty-three-year-old founder of social media agency Clipping.

The company is two-sided. On one side: A roster of high-profile clients, from Adin Ross to Ice Spice to IShowSpeed. On the other side: More than a thousand contract “clippers” from around the globe.

The clippers’ job? Identify key moments from a video, stream, or song; chop them up (potentially adding text); and upload them across anonymous accounts with usernames such as “Reelz_official.” Fujiwara communicates with his small army almost exclusively over Discord and pays them a revenue share: fifty dollars for every one hundred thousand views a clip receive across socials.

In other words: Clipping helps manufacture virality. “One recent campaign for Ross reaped 430 million views across 11,000 videos, created by 520 clippers,” the Times piece stated.

Fujiwara has grossed eight million dollars this year, as blue chip talent agencies like UTA and Capitol Music Group now employ Clipping’s services for their clients. “People used to buy commercials on TV, billboards, radio time slots…clipping is that for the modern era,” he says.

It’s a bold proclamation—especially when you consider that, yet again, social media regulation is lightyears behind that of TV, billboards, and radio time slots. Somewhere between shady and nefarious lies the simple truth that these anonymous, clipper-controlled accounts are not disclosing their source of funding.

This is important, because Fujiwara’s central pitch to clients is that they pay a fraction of the cost they’d fork over for Meta ads…and they don’t have to worry about those pesky, inauthentic-feeling “Click here to learn more” buttons. No, clipping is organic—or at least offers the semblance of organic popularity.

It’s therefore one thing when a Kai Cenat works with clippers, cutting up hourlong streams and spreading them across the Internet (as a non-Twitch viewer myself, I’m not ashamed to admit that I chuckled watching a clip of LeBron talk about Labubus). It’s another beast entirely when bad actors leverage the lack of clipping oversight to their advantage.

If this whole thing rings a bell, it might be because Andrew Tate rode a similar revenue share wave to commissioning clippers, as he became the world’s most famous misogynist in 2022.5 Another example: The online gambling website Stake has exploded over the last several years, partnering with streamers and celebrities—including Ross and Drake—to produce viral moments of large bets (the company was sued last month for providing its ambassadors with “house money”).

Who’s behind all the clips that drove Stake’s billion-dollar growth? You guessed it:

Now, do not take any of my words as an indictment on Fujiwara’s character. I don’t know him personally, and it’s not like he’s the only kid out there turning a quick buck (Net Influencer just ran a piece about a similar nineteen-year-old from Kansas; if the name of his agency, “Clipping Culture,” isn’t an indication that this cottage industry is a bubble ready to pop, I don’t know what is).

Nevertheless, the murky discussion surrounding payment disclosures does not stick out nearly as much as what a culture run by clipping says about our appetite for (mis)information. We’re all so busy, too busy to click through an AI overview or fact-check an account’s legitimacy. For a generation obsessed with feeling “authentic”—and aligning with others who present themselves in a similar fashion—we sure seem pretty content with gleefully accepting the source of our slop.

Why care about the truth if no one else will? Social media isn’t real.

4.

Standup comedian Maddy Kelly appeared on the popular shortform talk show Subway Takes this morning with a proclamation: “We need to start talking about how we’re gonna get off Instagram and Meta.”

Host Kareem Rahma initially agreed enthusiastically; he later walked it back in a half-serious comment. The discussion then centers around a basic irony (“The movement is gonna have to start on the platform itself,” Kelly states) before suggesting that the replacement for social media is…dinner parties.

Around this time last year, I wrote a piece called “The Internet is Real Life. It Doesn’t Have to Be.” In it, I mapped out my belief that positive change can happen at the local level if we reinvest our energy back into civic life—whether it be volunteering, participating in storytelling nights, hosting book clubs, and yes, attending dinner parties.

Something Kelly nails in the clip above is that these cultural shifts will take a collective buy-in. Online communities certainly play a vital role in spreading the message. Here’s how I concluded A Crash Course on Hank and John Green, our Issue Five cover story:

The path forward is daunting. But this pursuit has shown me that my desire to live in a more empathetic culture , within a more well-informed and a more loving society, isn’t as crazy (or isolated) as it may sometimes seem.

And that finicky feeling called hope? That might be the strongest level of influence any creator worth a damn could ever reach.

We need people and spaces to chart that path forward. The flesh-and-blood things that are real, after all.

If you made it this far, you probably noticed I switched things up a bit for the Sunday send. Instead of another Five Things I Think (I Think) column, you received a deep dive essay on a specific topic.

Was this heavily inspired by Derek Thompson’s recent piece Everything Is Television? No comment. But as you can probably tell, my intention here was to piece together disparate ideas and conversations that have been percolating. Let me know what you thought of it below.

Past that, a lot went into writing this piece. If you did enjoy it, consider sharing it with a friend. It goes a long way in supporting us on our mission.

P.S. Last blog, we asked you this: “Where do you find the creative pieces that leave the greatest impact on you?”

Here are the results:

54% said “Longform video (YouTube)”

31% said “Scripted television/film”

15% said “Books, zines, etc.”

0% said “Shortform video”

Thanks for reading! Shoot us a reply, comment, or DM if anything resonated with you in particular—we respond to them all.

Funny enough, LinkedIn is having a moment here, with “B2B influencers” coming under fire for improper disclosures.

It’s certainly on lawmakers’ minds: Two FEC members published a letter in 2023 criticizing the commission’s slow pace. They were in the minority and were left mostly unheard.