Five Things I Think (I Think) 🗞️

The Onion's new case study for print's glorious return

I’m feeling all sorts of nostalgia of late.

Maybe it’s because The Onion generated some buzz when they announced the relaunch of their physical newspaper. Maybe it’s because I recently went to see this summer’s hit coming-of-age film, Didi. Or maybe it’s because I dug into the archives to complete a big project I’ve been working on for a while.

All three of those subjects are featured in today’s send. And if you enjoy a particular essay, drop a reply—or send this to a friend who you think might connect with it. The support goes a long way!

— NGL

P.S. Last week, I wrote about my aversion to personal branding, why Strava is the best social media platform, and what Tyler, the Creator can teach us about marketing art. If you missed it, check it out here.

I think the bull case for print’s glorious comeback isn’t about what you think. In 1988, a pair of University of Wisconsin students founded a satirical weekly newspaper, running awe-inspiring headlines such as “Pen Stolen From Dorm Room Area” and “Raisins Now Hold Majority in California Senate.”

The following year, those students presumably got bored, because they sold their creation, The Onion, for sixteen thousand dollars. Since then, the publication has moved its headquarters to Chicago, changed hands several times (three times in the last decade alone), and shuttered its print operation in 2013.

Until a couple weeks ago, that is, when The Onion grabbed a relatively serious headline (for its standards). “No Joke: The Onion Thinks Print Is the Future of Media,” read a feature story in The New York Times.

While favorable coverage of the comedy newspaper’s print return showcased media members’ not-so-secret desire to make the format a thing again, audience sentiment appears to be positive, too. Several comments stood out to me when the NYT shared the story on IG:

“I think we’re at the point like Harry Potter’s magic universe. Yeah we can have tech do everything, but why? I hate reading on a screen.”

“Print will never die. Let’s just stop spreading that utter nonsense. It will just be more collectible and creative for those who survive thru innovation—not imitation. 🙌”

“More and more people are turning away from [the] internet as more and more tech leaders drift into fascism. Onion knows.”

The latter comment seems to be in tune with the mindset of Ben Collins, the new CEO of The Onion. A former disinformation reporter for NBC, Collins has given several interviews over the last couple weeks where he talks about the “fascist economy of information” and criticizes programmatic advertising—i.e. centering a media business around driving twenty million eyeballs to sponsored content, only to turn around and get paid pennies.

He’s betting on a more direct relationship with The Onion audience. For five dollars a month, subscribers get a print paper in the mail, invites to live events, and other perks. Collins still plans on building out a “pie chart” of revenue sources (like the publication’s YouTube channel), but claims “the foundation will now be the paper.”

Herein lies the elephant in the room. Instagram likes and cheery comments alone do not necessarily translate to product sales; when running a business sustainably, demand can’t just be chalked up to “vibes.” So what is the actual case for print in 2024?

From my point of view, the first point is a matter of input, not output. Open up a copy of GQ (which I love! and subscribe to in print!), and you’ll see seventy-plus names credited in making a single issue.

Unfortunately, what feels like a never-ending stream of layoffs in journalism indicates that only a select handful of the biggest media companies in the world can now support large headcounts. While The Onion’s newsroom has sadly shrunk from its peak of two hundred employees to its current-day roster of just fifteen (!!), the silver lining is that the low costs of running a modern media operation means that the team can move quicker and take bolder swings—like printing 40,000 copies of their revamped paper in the days leading up to the DNC and still needing to print more for new signups.

Which brings me to my second point. When many people think about magazines, they might conjure images of tabloids at the supermarket checkout line, or leafing through copies at an airport bookstore. This model of blasting magazines everywhere as a discovery mechanism made more sense in a pre-Internet era. Nowadays, the main reason some publishers still do this is so they can tell advertisers “we’re stocked in x amount of stores” and hope a check that dwindles with every passing year comes their way.

Yet what we’re also starting to see are smaller outlets tap into the counterculture roots of indie zines—and even pull a page or two out of streetwear’s hype-based model of artificial scarcity. One of the coolest models comes from a group of designers and YouTube creators, Never Too Small, who reached over a thousand paying subscribers before their first edition even launched. The new quarterly publication doesn’t just feature two hundred forty pages of original interviews and photography—it also acts as a storytelling mechanism for the brand, a journey they’re capturing on their channel as they invite viewers into their world.

At thirty dollars per quarter, this already comes out to roughly one hundred twenty thousand in revenue per year. Not currently enough to sustain a business alone…but as just one piece of the pie, for a small team of creators, it’s certainly nothing to scoff at.

I could talk about this topic forever—and begin quoting Kevin Kelly’s famous “1000 True Fans” essay. I could expand on why creative people love print, the magic found on this physical canvas and how it produces that elusive thing known as “taste.” I could cast aspersions on the actual likelihood that any of these experiments will work, and admit my biases that I, too, unabashedly believe in the format’s comeback based on “vibes” (and a desire to cut my own screentime in half).

But what I will conclude with is this: Most writers and creators aren’t looking for a tech company-style exit, and we’ve clearly seen what went wrong at the BuzzFeeds and Vices of the world when big VC money entered the picture. For those just looking to keep their heads to the ground and build a successful small business, going backwards with print actually presents an exciting new path forward—while making an outsized brand impact.

I think my love for print comes from Sports Illustrated. Since the start of 2022, I’ve made (or had a hand in making) six zines—four editions of Creator Mag, and two physical Publish Press newspapers. Yet High School Nate would’ve been quite surprised if you told him that that’s what he’d be creating a decade later.

Curiously, even while majoring in journalism, I didn’t contribute to any campus magazines in college (or ever). When I look back, though, some of the great writing I grew up on comes from tearing through copies of Sports Illustrated. Peter King’s “10 Things I Think I Think” column wasn’t just the source of this newsletter’s plagiarism—it was one of the reasons I started blogging online in the first place.

I don’t intend to be the “Print Guy” in the long run. But I do know why I wound up here.

I think Didi (2024) makes me miss 2008. One central tenet in the film bro discourse over the last several years is that the world’s most famous directors are choosing to set their stories in the past (see: Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch and Asteroid City, Martin Scorsese adapting not one but two of journalist David Grann’s history books) because the present is so uninspiring (see: cell phones).

How can modern characters get lost, or not know the answer to something, when the answer’s probably right at their fingertips? On top of that, how can filmmakers make smartphones and social media look, well, cinematic?

Didi flourishes because its director, twenty-nine-year-old Sean Wang, places his semi-autobiographical coming-of-age film in the same year he started high school. It’s a period when kids actually lived lives in the real world, then logged onto their home computers to upload amateur skate videos to YouTube and message friends on AOL Instant Messenger—not the other way around.

But Wang also succeeds by leaning into storytelling through screen captures on these platforms. We feel the anxiety during every second his main character, Chris, waits for his summer crush to stop typing and send an IM back; we relate to the insecurity when his mouse cursor scrambles to delete his old, cringey-titled YouTube videos so he can impress some older skateboarders.

This makes sense when charting Wang’s unique journey. His path to his feature film debut included four years post-grad at Google, where he developed commercials that explained features in products like Search and Pixel visually. From there, he directed a documentary short, “Have a Good Summer,” told entirely through yearbook photos, calls with his high school classmates, and simple hand-drawn animations.

Didi is inspiring to me because it’s proof that you can still tell good stories about modern culture via the traditional route, a look into the not-so-distant past through the lens of a young filmmaker with an intimate connection to his subject matter. When I went to South By Southwest earlier in March, I couldn’t stop hearing rave reviews about this movie, and the eventual ticket during its summer theatrical run was worth it. Say what you will of coming-of-age tropes—the communal feeling of watching, laughing, and celebrating an indie film alongside a packed theater is hard to top from the living room sofa.

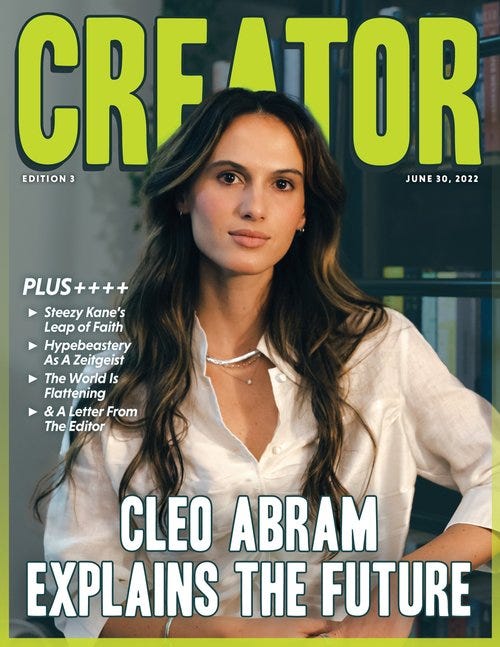

I think it’s fun to go back and read my old stories. I hung out with Cleo Abram a bit when she swung through L.A. a couple weeks ago, and we both remarked how much has changed since I interviewed her for a Creator Mag profile piece over two years ago.

That prompted me to go back and reread the story, an experience I often cherish—the more time that passes, the more I can appreciate my writing and the moment I was at in my own creative journey. So in the spirit of “being your own hypeman,” I excavated five of my favorite lines I’ve written in the past several years (shared here without much supporting context):

“Visual, rich storytelling crashes with pragmatic, historical analysis to form the basis of Cleo’s explainer journalism.”

— “Cleo Abram Explains the Future” (2022)

“The delineation of where the art itself manifests, too—as ‘user-generated content’ on YouTube, or a limited series on HBO, or anything and everything in between—feels less important than the character of the people creating it.”

— “The Year Creators Went Hollywood” (2024)

“It is, in all essence, the act of sacrificing one’s voice and its subsequent standing in a world where we can watch, read, and hear what everyone is thinking at any given moment, a little bit of everything, all of the time.”

— “Anthpo Closes the Yearbook” (2022)

“He loses out to known method actor Christian Bale, who goes through the process of cryogenically freezing himself in order to properly play Walt Disney in a 2019 biopic.”

— “The Alternate Timeline in Which J. Cole’s Dunk Goes In” (2019)

“While some things stay the same, his story, like all of us, is still being written, the same way Cole dissects every album on his show: Note by note, line by line.”

— “Note By Note With Cole Cuchna” (2022)

I love looking back at some of these lines, and hopefully this list continues to grow. But at the same time…

…I think I still have a long way to go—twenty years, in fact. Most Nobel Prize-winning writers, on average, produce their best work at age forty-five.

Progress may be a squiggly line, yet my belief is that the only thing within our control is to continue our commitment to creating, year after year after year.

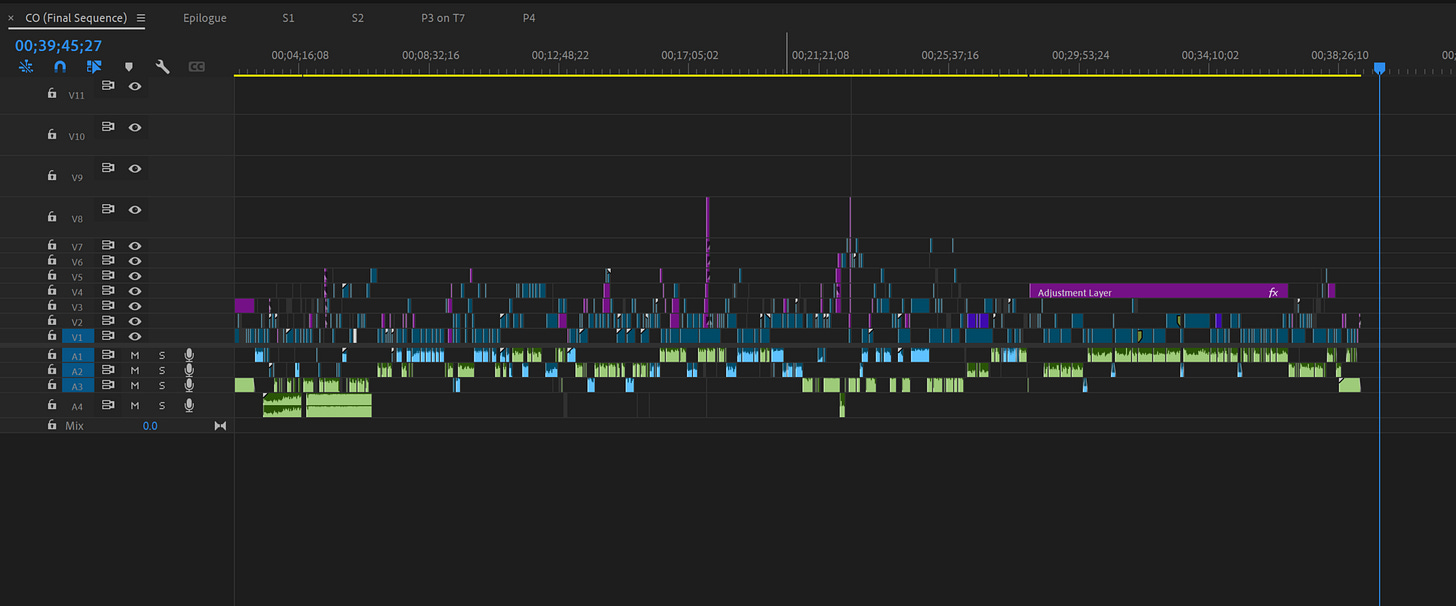

And one last note: Films and videos aren’t judged based on how robust their Adobe Premiere timeline is. At the end of the day, story is king.

Still, it felt really good to finally place all the different sequences in this project into one timeline and watch it back twice this week. I’ve been working on this short film on-and-off for about two years now, and I’m quite excited to share it soon.

When I showed this cut to Vicky, she remarked, “Ya know, all those times we’d go to a cafe on a Sunday or you’d stay up late editing, I obviously knew you were working on this. But it’s still crazy to watch it and realize, ‘Oh! Right! You were making something that entire time!’”

I’ll keep providing updates on this project every Sunday. For a hint on what it’s about, scroll up to the image at the top ☝🏻

Thanks for reading! And shoot me a reply or DM if anything resonated with you in particular—I respond to them all.