Five Things I Think (I Think) 🦅

The "journalist" versus "influencer" discourse is boring

I’m back in DC for my brother’s wedding—which is, well, today! This means that the words you are currently reading were not written last night, which goes against every pro-procrastination bone in my body.

I lived here for fifteen months—seventeen if you count Northern Virginia—before moving out to Los Angeles. I can confidently say how much I’ve missed elite (or even simply competent) public transportation. Along with running through Rock Creek Park and walking to a doctor’s appointment this week, I’ve also been taking the subway up to the great Cleveland Park Library, the same place I wrote a good chunk of Creator Mag.4 back in 2022.

It’s amazing what happens when you directly see your tax dollars in use—and take advantage of it. On that note, maybe it’s simply because I’m back in the district, but I’m feeling a little politics-adjacent this week.

— NGL

P.S. Last week, I wrote about print’s glorious comeback, the nostalgia of Didi, and the joy of re-reading our old stories. If you missed it, check it out here.

I think Joe Biden’s recent comments to journalists sound pretty Trumpian. Coming out the gate here a little fiery, so I’ll take a step backwards first.

Heading into college, I knew I wanted to work in media in some capacity, so I decided to go to journalism school and figure it out from there. In college, I met people who dreamed of becoming New York Times reporters and winning Pulitzers—my first real interactions with the more established media world.

Pretty quickly, I began to feel disillusioned from my coursework due to a belief that the increasingly fast-changing nature of the industry had left most of my professors (many of them veterans of newspapers and magazines) behind. That led me to spend most of my time on an online publication and some podcasts I’d started, as I thought I’d gain the most relevant experience by simply creating in mediums people were gravitating towards.

I was not a particularly good student in college. But curiously, the further I’ve gotten from graduating, the more I’ve come to value the importance of those lofty journalistic values that my professors used to preach—things like rigorous fact-checking and keeping powerful people accountable. The Fourth Estate may be crumbling, but it’s still an essential facet of a functioning democracy.

So when President Biden spoke to a group of roughly one hundred creator industry folks at the White House on August 14, it wasn’t the obvious statements he made that stood out. “You are the breakthrough in how we communicate,” he told the crowd, noting that his grandkids “don’t read the same newspapers or watch the same television.”

No surprises there. But a different interaction stood out: According to accounts from those present (as well as some attendees I chatted with), Biden labeled creators and traditional journalists as “competing camps.” And when some of the journalists who had been granted press pool access shouted out unrelated foreign policy questions as Biden spoke, the White House removed them…an action some in the group cheered.

In the grand scheme of things, this interaction may seem miniscule in relevancy. Yet there’s a lot to unpack. For one, I generally think that most people don’t even know how journalism gets done anymore because people don’t consume journalism. Biden’s team has largely shielded him from giving many interviews over the last couple years. Keeping those in power accountable, therefore, is not limited to when it’s most convenient to ask hard-hitting questions.

Past that, however, is the fact that Donald Trump’s language of labeling media outlets “fake news” and “the enemy of the people” isn’t quite as novel as it was in 2016. Adopting this language has become commonplace whenever individuals across industries and the political spectrum view journalists as antagonistic, and using catch-alls like “the elites” is an lazy lob that even Biden has leaned into when describing his real enemy: “the pundits.”

This is easier than ever before because traditional media has never been weaker. As Jay Caspian Kang wrote in The New Yorker in July, people haven’t just lost trust in the contents of reporting. They’ve “lost faith in the entire apparatus of the press”:

People once relied on newspapers for all sorts of things, and though much of that information—sports scores, movie and TV listings, classifieds—weren’t exactly vital, they helped to build a trusting relationship.

That’s gone, and it’s not coming back. Baseball games update by the pitch, politicians make statements on social media, and attention, which used to be meted out by the media, is now under the watch of algorithms.

So why does any of this matter? Well, it’s because those “trusting relationships” have splintered across an infinite amount of people and sources online. And subsequently…

…I think the “journalist” versus “influencer” discourse is boring. A lot of pieces emerged following the Democratic National Convention’s decision to credential two hundred social media-first creators this year. Journalists decried a lack of space to work and even outlets to charge their laptops during their week in Chicago; reports suggested that some creators were invited to exclusive yacht parties where they hobnobbed with high-profile guests like *checks notes* Gwen Walz.

Now, that’s not a cheap shot at Gwen Walz—she seems lovely, and we need more teachers in politics! It’s more just a comment on the scope of those pieces (some of them bordering on condescending) feeling overblown.

Because the modern media and entertainment ecosystem has become an all-encompassing blob called “content” where everything is now competing for the same resource: attention. Sure, there’s exceptions. On the highbrow end, a yearlong investigative piece or a Christopher Nolan film; on the lowbrow end, a fifteen-second TikTok your two-year-old nephew records on your phone.

Replacing the black-and-white distinction of “journalist” versus “influencer” with something like “informer” versus “entertainer” might be a step in the right direction. But try asking someone my age to distinguish between those two buckets when the most “traditional” news source they consume is John Oliver’s monologues on YouTube.

To sum: I’m not particularly interested in labels. The practice of exploring and interrogating the world around us—then packaging and translating that information in a way that resonates with audiences—is more relevant than the outlet someone writes for or the degree they possess.

Yet something journalism school did give me and my peers was several years to try things out—and sometimes even f*ck up when no one was watching (for the most part). Looking back on it, that learning period was really important, regardless of whether or not I consider myself a capital-J journalist.

And most of the capital-J journalists I know went down this career path because of a idealistic belief in the Fourth Estate—certainly not a misbegotten understanding of salary potential or claims of intellectual élitism. So if more and more folks are quickly gaining trust online and building exciting entrepreneurial ventures by taking the form of “influencers”—for the purpose of this essay, YouTube creators, TikTok personalities, and Substack writers who are at least mildly interested in covering the “news”—then those folks just need to be held to the same standards of fact-checking, of not spreading misinformation and not sacrificing accountability for access. It’s that simple.*

Now, for a less self-serious topic.

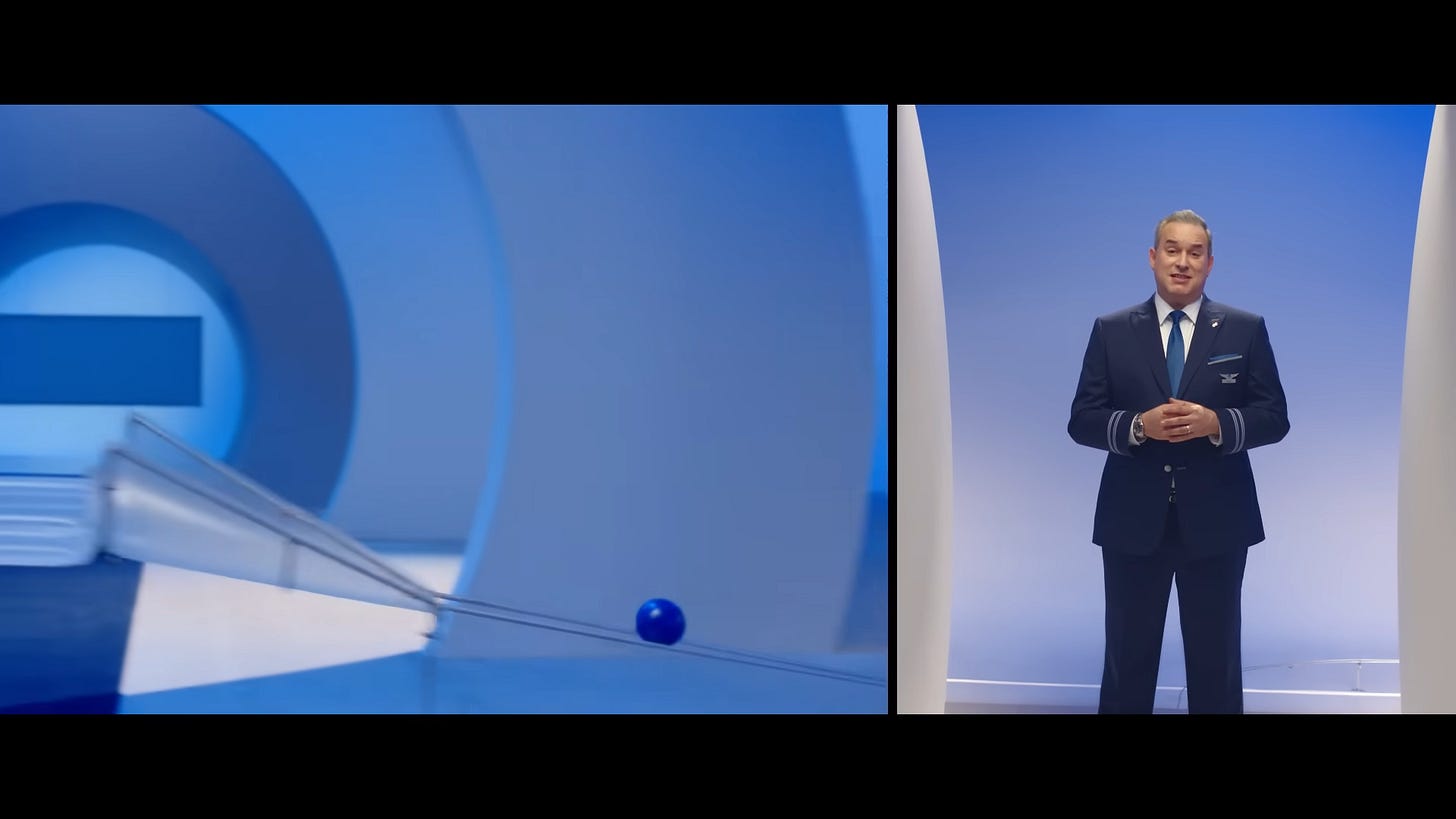

I think United Airlines’ safety video needs more Subway Surfers. In the last month, I’ve found myself sitting on United flights several times, entranced by their new safety video:

Yup, it’s basically a five-minute video following a fun, inoffensive Rube Goldberg machine—that happens to feature some airline safety info in between, shared by actors who seem nice enough.

United probably doesn’t just think our attention spans are clapped. They must know it (and have the data to prove it). Just look at this screenshot:

I have no idea what the fella on the right is saying. But wow! Look at that ball roll down that ramp!

At this point, I propose that the airlines just go all in, tapping into brainrot and maximizing retention at all costs. Using my top-notch Photoshop skills, here’s the slight tweak I would make for this video’s sequel:

Ahhh. I feel safer already.

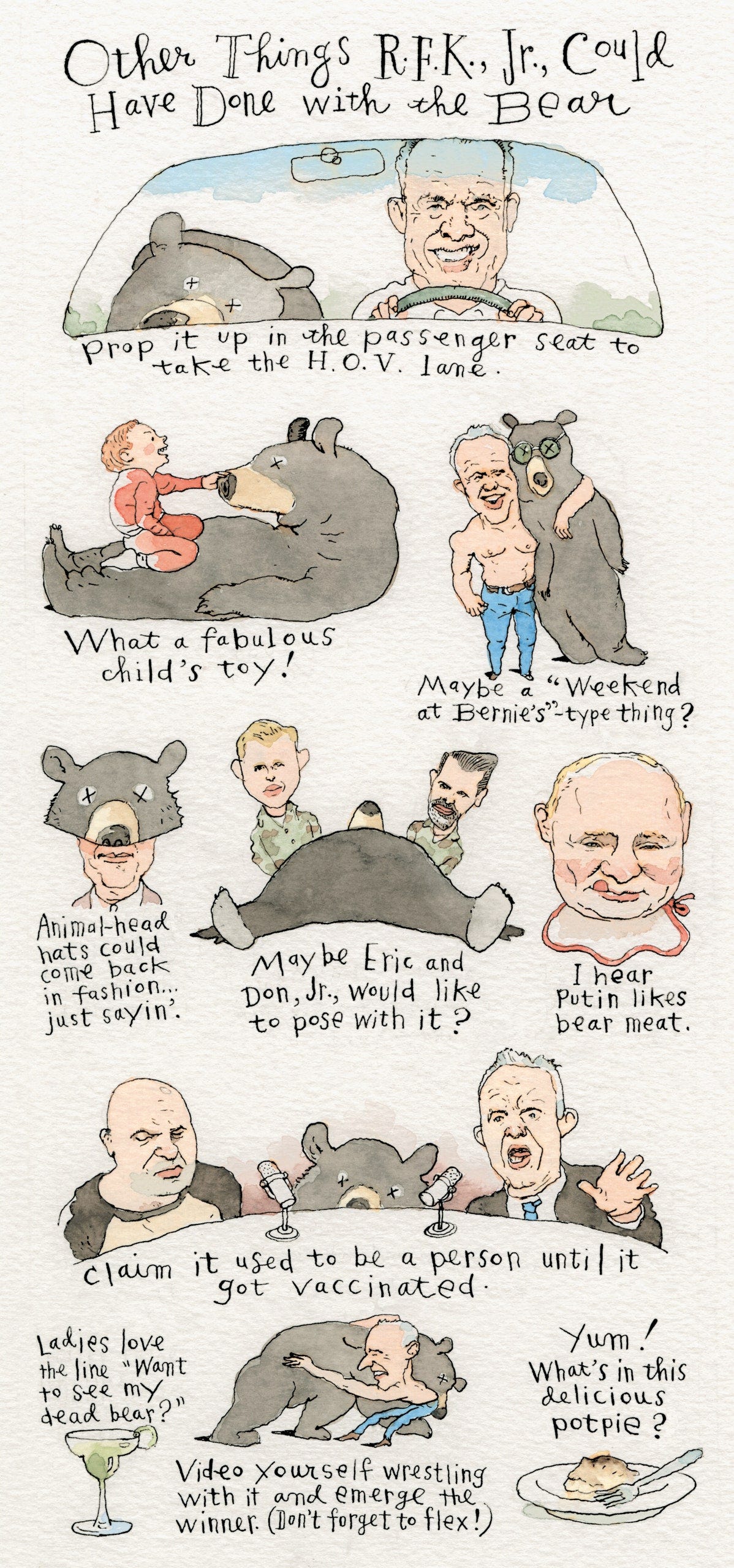

I think whoever runs Robert F. Kennedy Jr’s PR deserves a raise. Not because they’ve done a good job for him (I’d argue they haven’t!) but because they’ve provided the rest of us with some A+ comedy these last several weeks.

To recap, the man who said in May that a worm ate part of his brain somehow topped that anecdote in August, when a New Yorker profile revealed that he’d dumped the carcass of a dead bear cub in Central Park ten years ago—a mystery deemed a car accident at the time. “Maybe that’s where I got my brain worm,” Kennedy unironically told The New Yorker’s Clare Malone.

Though I misspoke. Because in an attempt to somehow get ahead of the profile before its release, it was actually Kennedy who revealed the story first, posting a three-minute video on X where he recounted what happened to…the problematic comedian Roseanne Barr. In his kitchen.

With the way Internet cycles work, by now, this is all old news. Plenty of people got their jokes in, including—but not limited to—the legendary comedian Steve Martin, who wrote a tidy infographic explaining all of the alternate things Kennedy could’ve done with the bear (the pickup line “want to see my dead bear?” is an all-timer).

It couldn’t have possibly gotten any weirder from there. Right?

Well, last week, old comments from Kennedy’s daughter Kick resurfaced where she described the time Kennedy sawed off the head of a dead whale and strapped it to their car, driving it five hours so he could “study it.”

“Every time we accelerated on the highway, whale juice would pour into the windows of the car, and it was the rankest thing on the planet. We all had plastic bags over our heads with mouth holes cut out, and people on the highway were giving us the finger.”

This is very much illegal, and honestly, a little sad. In the grander scheme of Kennedy’s vaccine-denying, COVID conspiracy arc, though, if you don’t laugh (a lot!) you’ll cry.

I think truth inspires fiction much more than we give it credit for. I just finished reading Naomi Alderman’s 2023 novel The Future. It’s a sci-fi book that predicts what happens in a not-so-distant future where a crop of tech oligarchs—convinced that the end of the world is nigh—spend all their money acquiring land and building bunkers.

Of course, it’s well-documented that billionaires—from venture capitalist Peter Thiel to the original influencer, Kim Kardashian—are laying ground on their own underground luxury compounds, fitted with indoor pools and artificial sunlight. While waiting in the doctor’s office on Wednesday, I flicked open this week’s edition of The New Yorker** to find a story where a journalist, Patricia Marx, actually toured a property in Montana with a real estate agent who specializes in “bunker sales.”

“On the drive back to my hotel, I asked [the agent], partly as a joke, where the weapons were kept. She explained one of the regular gambits of the bunker-selling trade: ‘It’s very common to put in the listing that there are hidden doors and bookcases and rooms that will be shown to the buyer only once the property is purchased.’”

Sci-fi books like The Future do a masterful job of highlighting all the social and political upheaval the powerful cause through their actions. Thing is, they lose a bit of that wow factor when our present is already so damn weird (see: R.F.K. Jr.).

Thanks for reading! And shoot me a reply or DM if anything resonated with you in particular—I respond to them all.

* Of course it’s not actually that simple—I just didn’t want to belabor this portion too much. I do think the #discourse stemming from this Eric Newcomer tweet offers some productive follow-up reading for those interested, though.

** For those keeping score at home, this is my third reference to a New Yorker article in this newsletter alone. Vicky likes to say I’m a “New Yorker élitist” for how much I read (and reference) the magazine. I like to say that I gravitate towards good storytelling.